Did employment numbers change the equation for the Fed?

Chief Economist Eugenio J. Alemán discusses current economic conditions.

Now that the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) released the delayed October and November nonfarm payroll numbers, do we know more about the US labor market than we knew before the release? Probably not. The release of both the October and November numbers does help to cement our previously held view that the labor market has been weakening but probably does not add much more than that. This means that the Federal Reserve (Fed) will probably have to wait for the December employment number, which will come out on January 9, 2026, to have a perhaps better understanding of the labor market at the end of 2025.

Will cutting rates in January of 2026, which is when we have the next Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting, do anything to relieve the labor market from its ailments? No. Monetary policy acts with long lags, so nothing it will do in January will change the state of the US labor market. After having cut rates three times this year plus 100 basis points last year, Fed officials are probably expecting no further deterioration to the labor market or economic activity next year, as shown by their updated Summary of Economic Projections (SEP). It is unlikely that this week’s report will change their views.

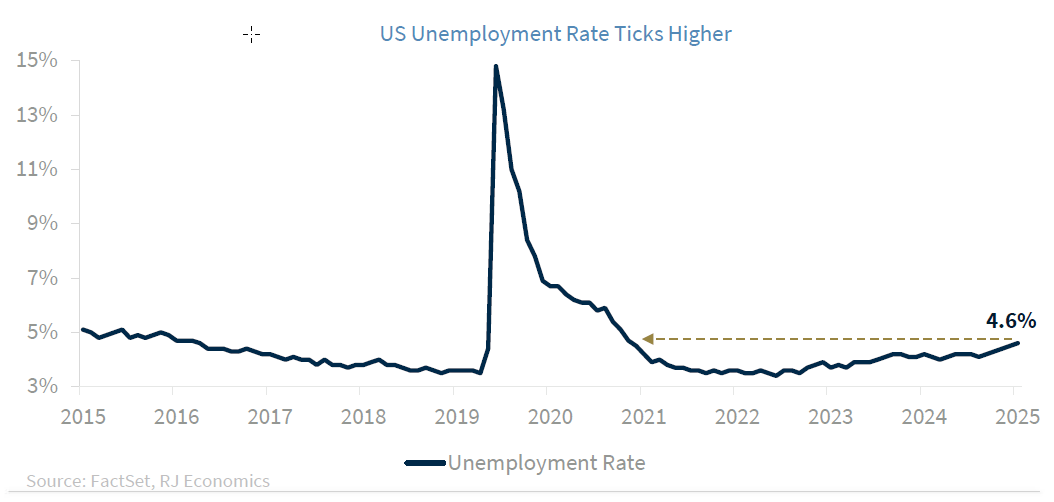

Perhaps the more troublesome data point from this week’s employment report was the notable increase in the rate of unemployment in November to 4.6% compared to a rate of unemployment of 4.4% in September. Bear in mind that the latest SEP had a range for the rate of unemployment for 2026 between 4.2% and 4.6%, which means that the rate of unemployment already hit the top of the 2026 range before the year even began. Additionally, we will never get to see what happened to the rate of unemployment in October because of the government shutdown. Thus, Fed members will probably not cut rates in January, given the incomplete nature of this data point release.

Furthermore, the increase in the rate of unemployment seems to have been driven by a 3.1 percentage point increase in the rate of unemployment for teenagers, from 13.2% in September to 16.3% in November, plus a relatively strong increase in the rate of unemployment for Blacks/African Americans, which increased from 7.5% in September to 8.3% in November.

The increase in the rate of unemployment in November would have probably put the Sahm Rule, which is an indicator of a potential recession, very close to its trigger level. The biggest issue with this trigger indicator is that we don’t know, and will never know, what the rate of unemployment was for October, so for now there is no way to calculate if the three-month moving average increase in the rate of unemployment will be above the 0.5 percentage point until we get longer, uninterrupted data.

What to make of the CPI numbers for October-November?

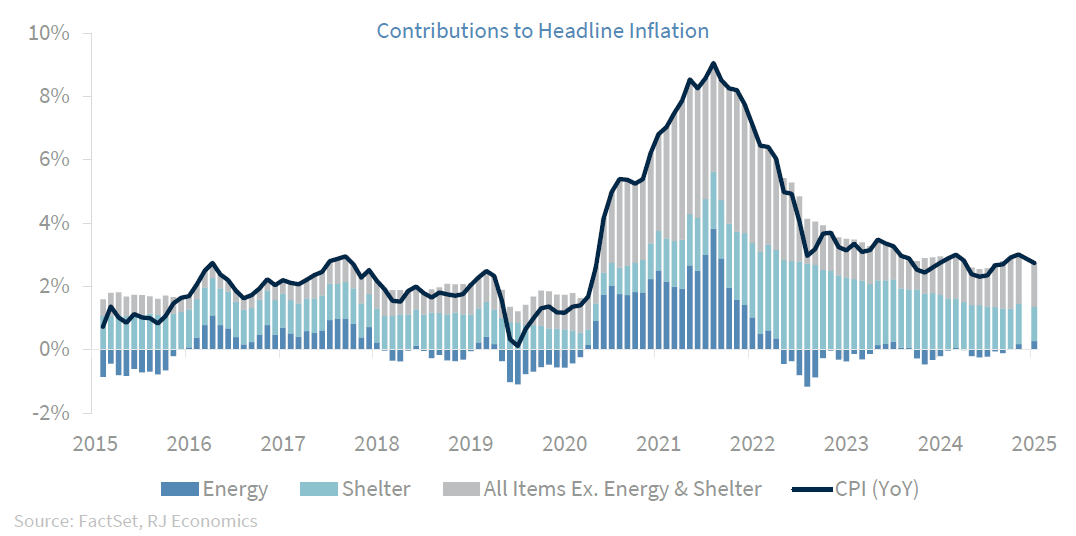

The release of the delayed November Consumer Price Index (CPI) report added further data confusion for Fed members, and although markets will start pushing for more cuts due to the “benign” two-month reading released this week, we believe the Fed will probably rely more on its own models than allow these latest data points to determine the path forward.

We have been arguing for a very long time that the disinflationary process, ex-tariff effects, has continued in the background, and that was the main reason we were advocating for the Fed to lower interest rates this year. However, we caution that the reported number in November is probably too good to be true and would want more evidence to confirm this accelerating pace of the disinflationary process. If we are this cautious, then Fed members, who have the actual responsibility of conducting monetary policy, are probably going to be even more cautious about the path for rates.

This was the first time in recorded history that the US has missed a monthly inflation reading, and this means that there is no other historical precedent we can rely on for some pointers on how to interpret this result. Thus, Fed members will remain cautious on changing their view on interest rates until information/data flows stabilize after the government shutdown.

Until this happens, the employment readings coming out during the first half of the year will carry the bigger weight on Fed decision makers. Since fiscal policy will remain highly expansive during 2026, they have to be careful not to add fuel to the fiscal fire, so to speak. With regards to inflation, they need to wait until the data stabilizes from what we have seen this week. It is highly unlikely that inflation has slowed down as much as this November report indicated. The report had a very weak reading in shelter costs during the period, which is highly unlikely due to the way the BLS calculates them. We hope they did not change the way they calculate shelter costs at a time when we already have uncertainty from the lack of data collected in October. Some are arguing that the BLS may have assumed no change in shelter costs during the two months while there is a chance that the late start to price collection in November may have affected the calculation just because of an already active seasonal price reduction cycle compared to a normal November data collection cycle. Additionally, even Fed Chair Jerome Powell warned last week that the central bank would take a “somewhat skeptical eye” to the November data because of the impact of the shutdown. We don’t really know but hope the BLS would add some explanations going forward. At the same time, it is possible that inflation reaccelerates in December and into the first quarter of the year so the Fed will be very careful under these conditions.

We also want to caution that the weight of shelter costs in the CPI is close to a third of the index while the weight of shelter costs in the PCE price index is about 13%. This means that the effect of slowing shelter costs on the PCE price index is much less than in the CPI, and the Fed targets the PCE price index rather than the CPI.

Economic and market conditions are subject to change.

Opinions are those of Investment Strategy and not necessarily those of Raymond James and are subject to change without notice. The information has been obtained from sources considered to be reliable, but we do not guarantee that the foregoing material is accurate or complete. There is no assurance any of the trends mentioned will continue or forecasts will occur. Past performance may not be indicative of future results.